Transit-Induced-Gentrification

Evidence from East London neighbourhoods affected by the extensions of London Overground and Dockland Light Railway

Institution: Department of Land Economy, University of Cambridge

Time: Jan.2023 - July. 2023

Project location: East London, the United Kingdom

This research has been presented at the panel session Quantifying Gentrification and Displacement: Big Data and Other Data in “Gentrification & Displacement:What Can We Do About It? An International Dialogue”, International Conference on Gentrification, Boston, MA

Abstract

With transit-oriented development (TOD) becoming a widely adopted paradigm in urban planning, the public sector’s investment in railway-based public transport networks has increasingly been deemed a catalyst for urban regeneration. This trend has raised concerns regarding the triggering of gentrification and displacement in districts around the transport node, which could exacerbate social inequalities in terms of access to public transport. However, there is no sufficient quantitative evidence in support of this hypothesis, especially when it comes to indicators beyond housing prices. Using a panel dataset of the seven East London boroughs from 2004 to 2015 at Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) level, this research measures the extent of gentrification and displacement resulting from the extensions of the London Overground and the Dockland Light Railway with five different dependent variables based on the Difference-in-Differences (DID) method. The result reveals significant increases in median housing prices and median household incomes, suggesting the uplifted socioeconomic conditions induced by the transportation programme in LSOAs located within a 1 km radius of the stations. A significantly decreased level of population retention rate also indicates the displacement of the original communities, even after controlling for the impact of the 2012 Summer Olympics. Concurrently, the new property development around the stations is estimated to bring additional impact on such income uplifting and population relocation, uncovering the role of transit-oriented property development as an accelerator in gentrification. A follow-up quantitative modelling of each transport line and a K-means clustering of the studied sample demonstrates the estimated gentrification and displacement are more conspicuous along the London Overground, featured by new-build gentrification around the stations. This provides empirical evidence that captures the processes of transit-induced gentrification in the East London neighbourhoods, underscoring the urgency and necessity for policymakers to consider these implications in future transit-oriented urban regeneration programmes.

Keywords: transit-oriented development, gentrification, displacement, public transport, East London*

Key Findings

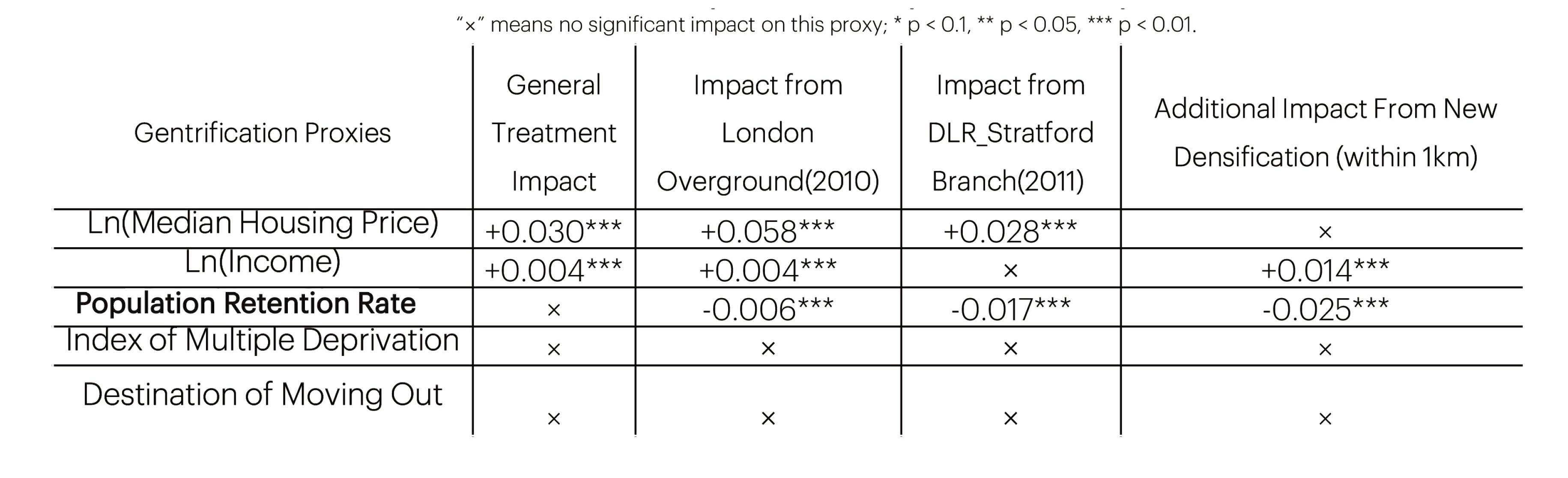

The research uncovers that the gentrification and displacement happened in East London around 2010s is highly connected with the state-led transportation development projects and the following new construction under the concept of TOD(transit-oriented development).There are mainly two takeaways:

(1) There are significant housing price increase and population retention rate drop around both lines, as well as an uplifted income level around London Overground after the extension programmes, all of which protray the process of gentrification and displacement.

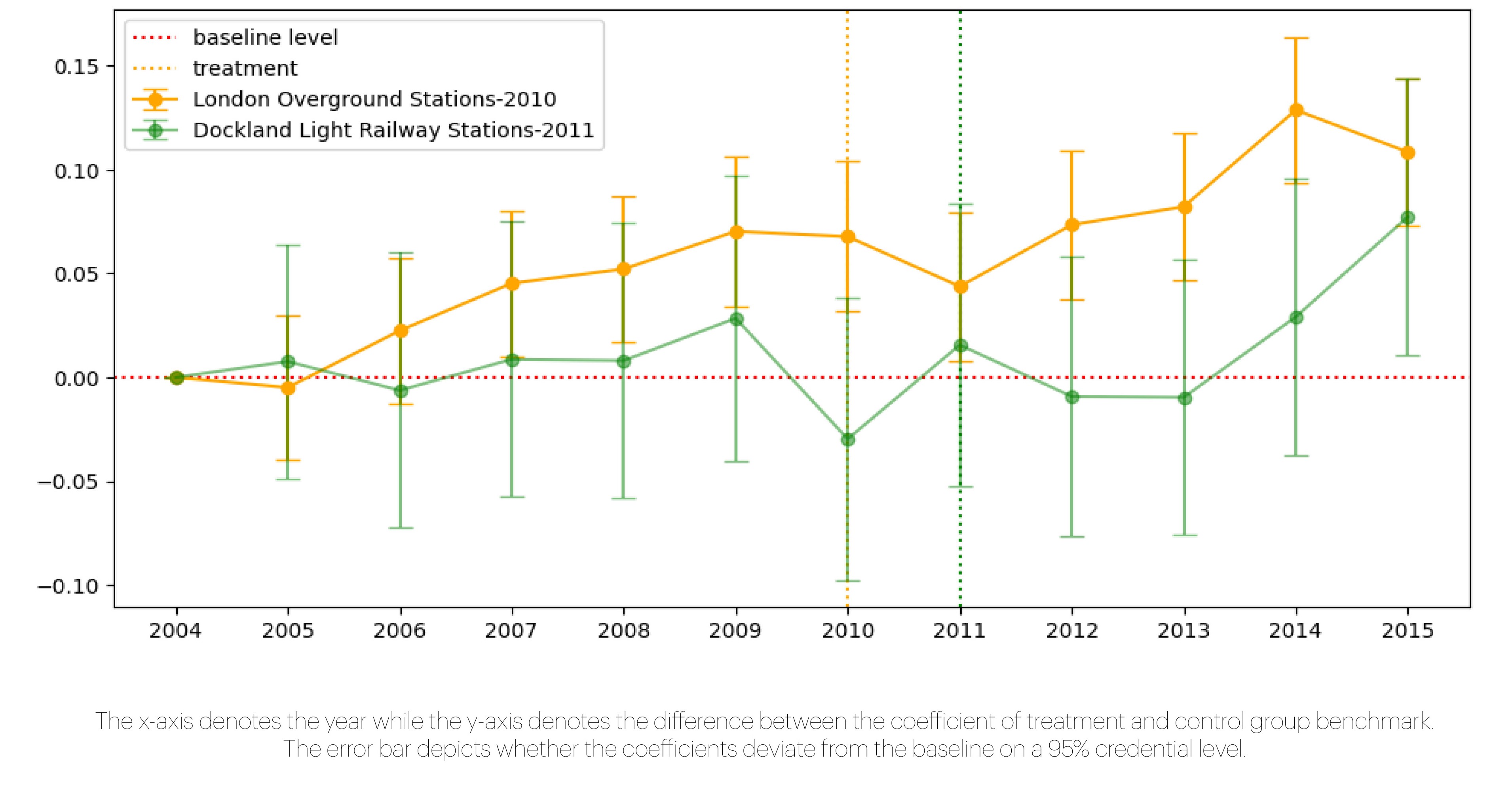

In the analysis of annual impact on the neighbourhoods along these two lines separately, heterogeneity is identified. For instance, housing prices surrounding the London Overground began their ascent after 2006, coinciding with the public announcement of the ‘London Overground’ project. In contrast, the areas around the Dockland Light Railway saw a delayed surge, with prices taking off only after the end of the London Olympic Games. This observation underscores the intricate interplay between transportation development and various policy initiatives, as well as investment activities.

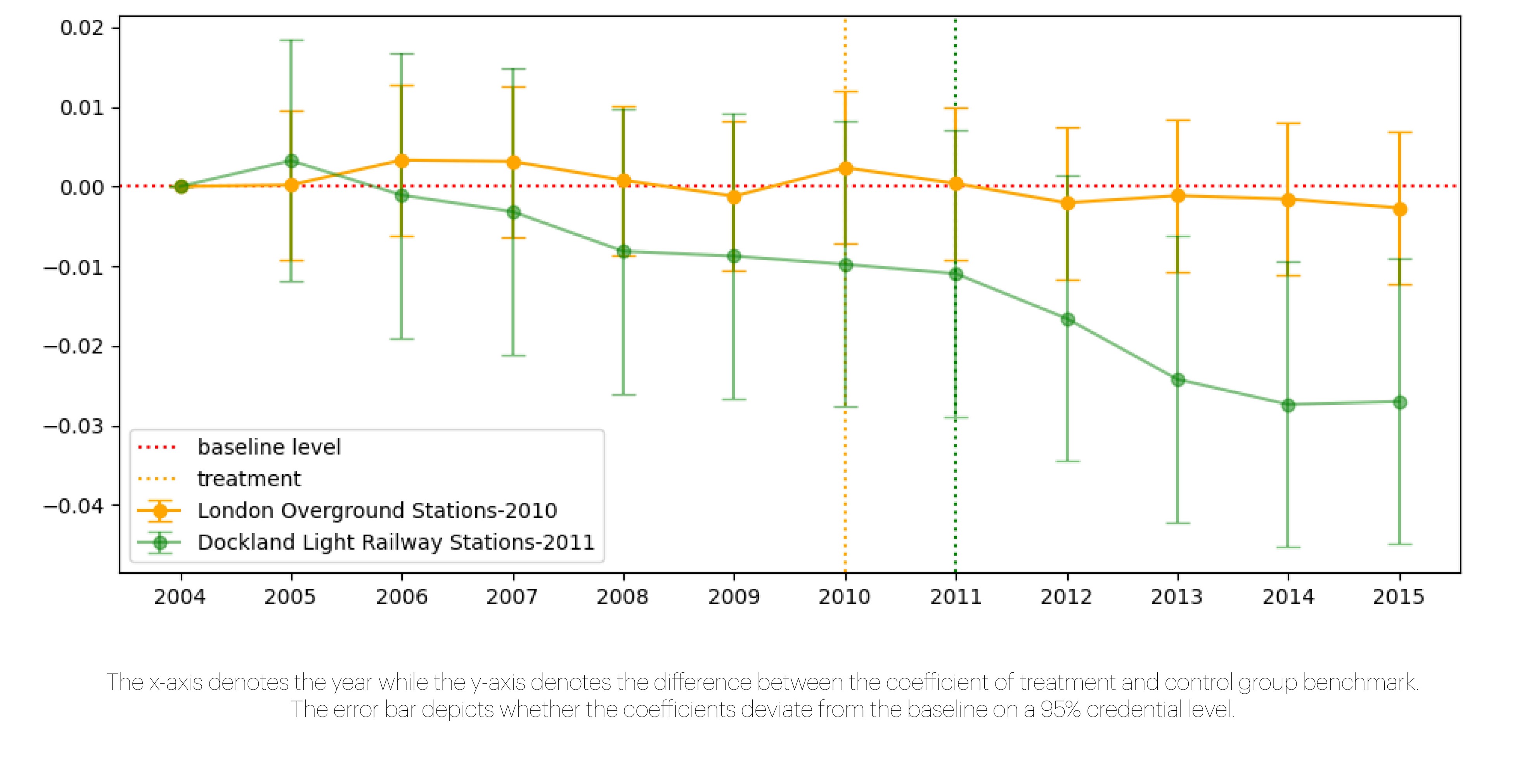

Additionally, we found a consistent decline in population retention since the opening of these new lines, with the effect being more pronounced around the London Dockland Light Railway each year. It’s worth noting that the baseline level already accounts for the impact of other control variables, suggesting that the absolute level of housing price increase and population loss may be even more substantial.

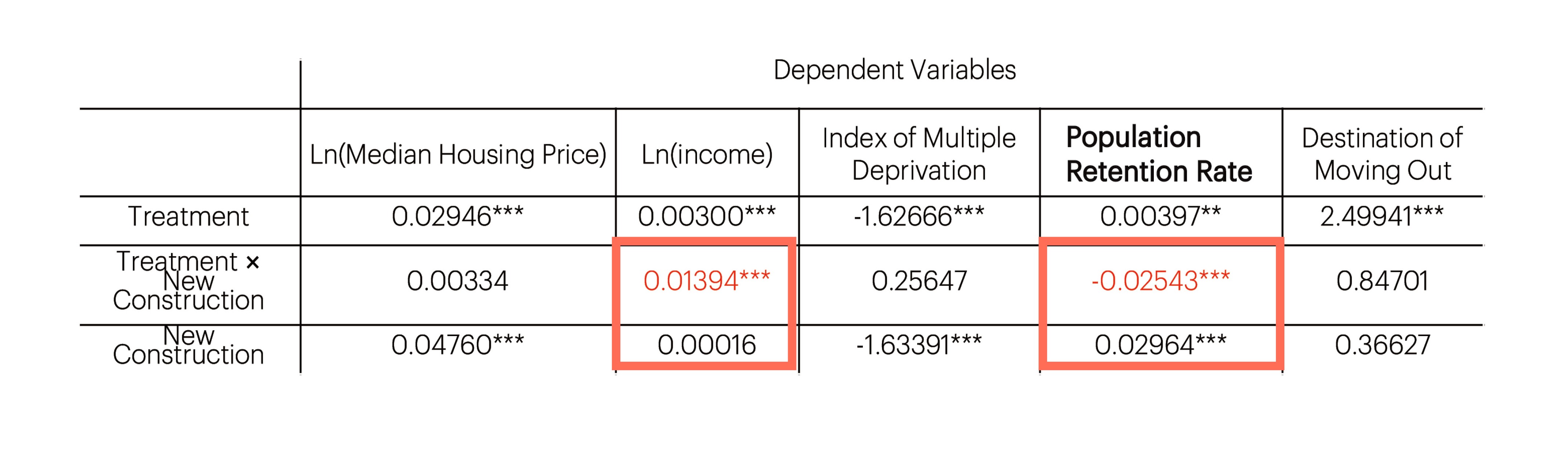

(2) New constructions around the stations, driven by the TOD concept, play an extra role in accelerating gentrification and displacement

The table above provides insights into the impact of new construction within a 1km radius of the new stations. It highlights a noteworthy trend where such development has resulted in a substantial increase in income, accompanied by a significant drop in the rate of population retention, which has not been observed in other neighbourhoods with new construction. This shows the extention of London Dockland Light Railway and London Overground together with the transit-oriented property development around them is more likely to displace economically disadvantaged residents from their original neighborhoods, adversely affecting their access to the public transport network instead of benefiting them.

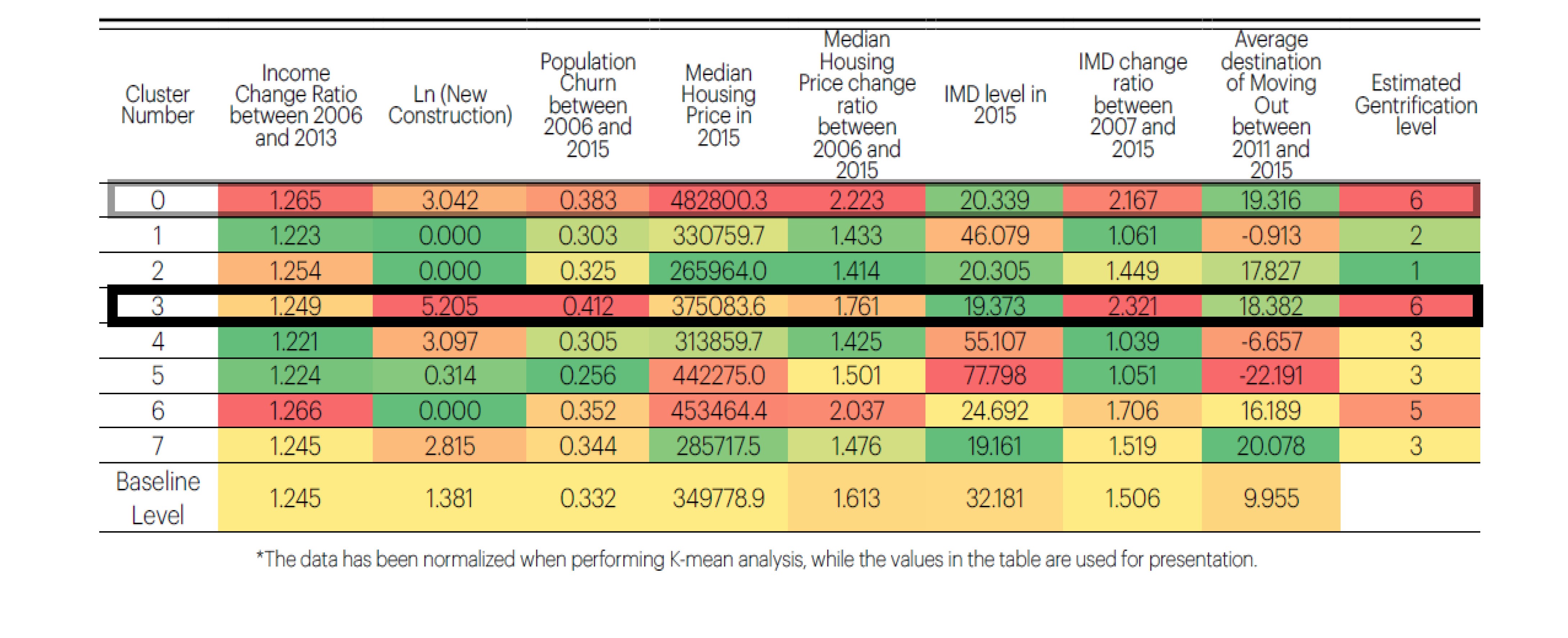

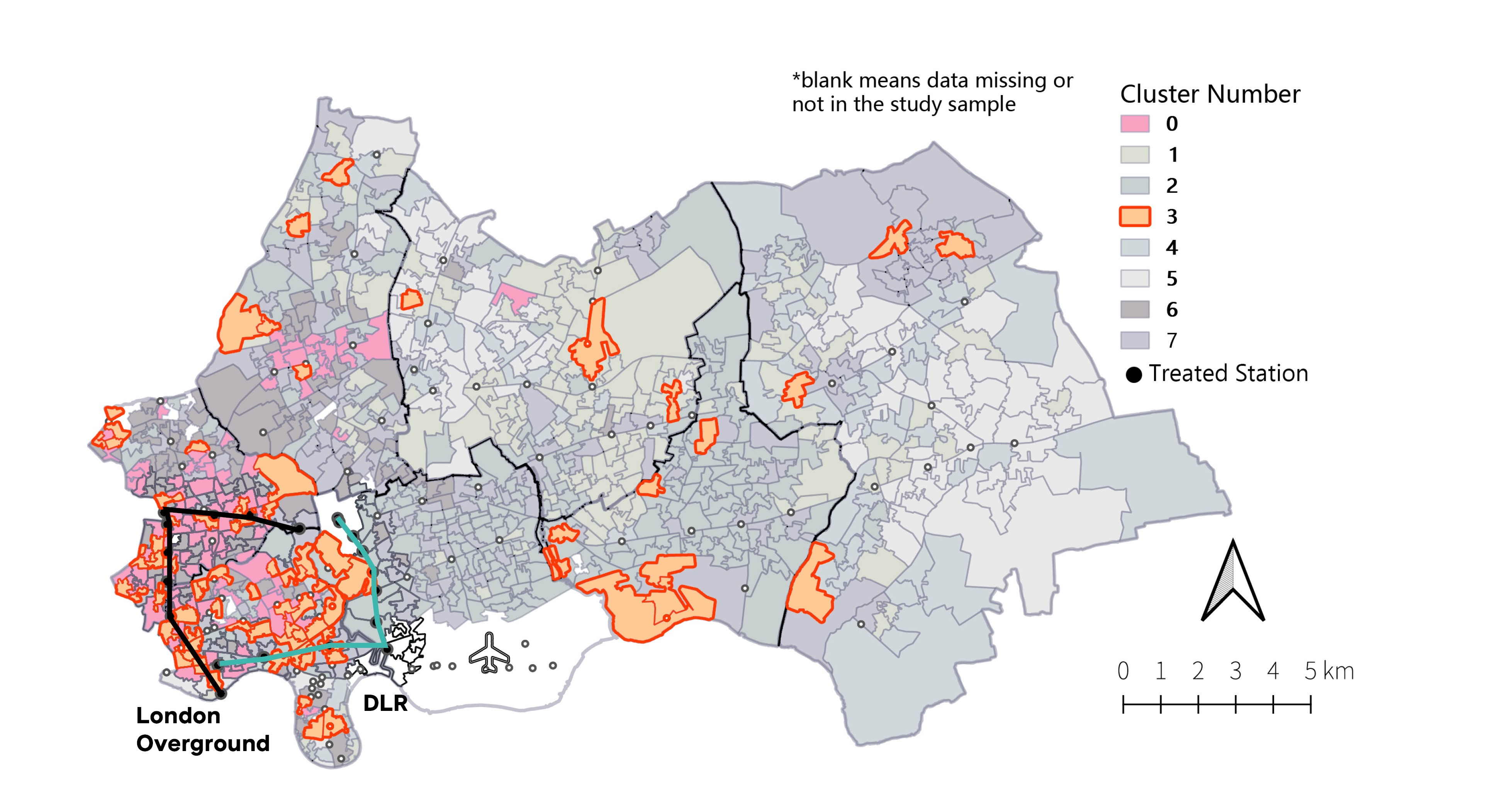

The further K-mean cluster analysis result has divided all the LSOAs in East London according to the level of gentrification indicators. While Cluster 0 is identified with more intensed level of gentrification, Cluster 3 shows higher level of new constructions(labelled as “new-build gentrification”).

By highlight the two most intensively gentrified clusters of neighbourhoods on the map, all the LOSAs around London Overground demonstrate the gentrification features(with the colors of the two clusters), with those directly adjacent to the stations falls into the cluster of “new-build gentrification”. This indicates how these areas are more likely to be favoured by the transit-oriented development and related investment.

Policy Recommendations

Although the results suggests the potential connection between public transportation development programmes and gentrification issues, it does not neccessarily mean that such programmes should be abandoned or apposed. In contrast, more planning interventions has to be well considered to ensure the public transportation projects could truly serve those vulnerable groups instead of building purely for financial or economic purpose. Future policymaking may consider:

1) Housing Price Control around the public transportation node.

This might be done through either controlling the unnecessary luxury refurbishments around the stations(similar to the “Milieuschutz-Gebieten” set up in Berlin) or introducing a rent brake(see the “Mietpreisbremse” introduced in Berlin) around the transportation hub areas to minimise the displacement caused by housing affordability.

2) More Affordable Housing as Planning Obligations

More affordable housing programmes should be embedded as planning obligations(eg.through section 106) for the property development around the transportation hubs to minimize the displacement risks caused by new-build gentrification.

3) Planning Ahead and Collabrative Decision-making

The decision of transportation development should not be made solely by the state or local concils for the sake of economic development. The decision-making process should be more transparant so that more actors could involved in advance. This allows an early stage negotiation where the increased land value could be captured properly for the benefits of local people instead of extracted by the developers.

Summary Report

More information regarding the research design and methodology please refer to the summary report below:

Acknowledgements: The data for this research have been provided by the Consumer Data Research Centre, an ESRC Data Investment, under project ID CDRC 1441, ES/L011840/1; ES/L011891/1 This research is based on my MPhil dissertation conducted under the supervision of Dr Sabina Maslova. I would also like to thank the valuable input from Professor Keren Horn, Professor Helen Bao, Dr Li Wan and Dr Davide Luca to this research.

Look forwards to getting in touch with you!

☕ Powered by github

based on Pudhina theme by Knhash 🛠️